January 25, 2026

The Case Study Houses program wasn't just another architectural trend; it was a full-blown experiment born out of necessity and optimism. Sponsored by the influential Arts & Architecture magazine, it ran from 1945 to 1966 and set out to solve a very real problem: the massive housing shortage facing America after World War II.

The magazine commissioned the biggest architectural names of the day for a seemingly simple task: design and build model homes that were both affordable and efficient. These weren't just blueprints on paper; they were tangible prototypes for modern living, and in the process, they became legendary symbols of mid-century modernism, celebrated for their clean lines, industrial materials, and wide-open spaces.

Picture it: America is just emerging from the long shadow of World War II. There’s a palpable sense of hope in the air, but also an urgent, practical crisis. Soldiers are returning, new families are starting, and there simply aren't enough places for them to live. This is the stage on which one of modern architecture's most defining movements was launched.

In 1945, John Entenza, the visionary editor of Arts & Architecture, kicked off the Case Study Houses program. It was a bold, head-on response to the housing crunch. Entenza wasn't just interested in putting roofs over heads; he wanted to completely reimagine what a home could be for the average American family.

At its heart, the idea was brilliantly straightforward. Entenza challenged leading architects to create homes that hit a trifecta: affordable, replicable, and genuinely beautiful. These weren't intended as extravagant one-off mansions for the wealthy. Each house was a "case study," a living prototype designed with the potential for mass production in mind.

The entire program was built on a forward-thinking, modernist philosophy. It championed a few core principles that would go on to define the whole mid-century aesthetic:

"The House must be capable of duplication and in no sense be an individual 'performance'," declared the program's first announcement in Arts & Architecture. This statement made the mission crystal clear: create scalable solutions, not just personal architectural showpieces.

Ultimately, the Case Study Houses program was about bringing great design to the masses. It made the radical proposition that thoughtful architecture wasn't a luxury, but a vital part of a better, more connected, and more efficient way of life.

The architects were tasked with designing homes that reflected the informal, open lifestyle of post-war America. This meant ditching stuffy, compartmentalised rooms for open-concept floor plans that let family life flow freely. It also meant using floor-to-ceiling glass to frame the outdoors and sliding doors that opened entire walls to patios and gardens. This groundbreaking experiment would go on to influence home design for decades, proving that a house could be far more than shelter—it could be a blueprint for living well.

A grand vision is nothing without the brilliant minds to bring it to life, and the Case Study Houses program attracted some of the most forward-thinking architects of the 20th century. These weren't just designers; they were philosophers of space and artists who used steel and glass as their canvas. Their collective genius is what turned a magazine's bold idea into a tangible architectural legacy.

Each architect brought a unique perspective to the table, yet they all shared a deep commitment to modernism's core ideas. They believed in functional beauty, the honest expression of materials, and creating homes that truly served the families living inside. You can see their work as a direct conversation with the Southern California landscape and the informal, sun-drenched lifestyle it encouraged.

Perhaps no names are more synonymous with the spirit of the program than Charles and Ray Eames. They were more than just architects; they were true polymaths, moving seamlessly between furniture design, film, and industrial arts. Their contribution, Case Study House #8, was uniquely personal—it was their own home in Pacific Palisades.

Completed in 1949, the Eames House is a masterclass in modularity and industrial charm. It’s not a single structure but two double-height boxes—one for living, one for work—separated by a sunny courtyard. The Eameses famously used off-the-shelf industrial parts like steel beams and factory windows, proving that mass-produced materials could create something elegant and deeply personal. Their home became a living laboratory, a space where design and daily life were one and the same, its vibrant interior a lively contrast to the rigid exterior frame.

If the Eameses represented playful ingenuity, Pierre Koenig embodied the dramatic potential of industrial materials. Koenig was a true believer in steel, seeing it not just as a structural necessity but as a beautiful aesthetic element in its own right. He ended up designing two of the most famous case study houses ever built.

His masterpiece, Case Study House #22 (the Stahl House), is arguably the program's most iconic image. Perched daringly in the Hollywood Hills, the house appears to float over the city lights below. Koenig achieved this breathtaking effect with a minimalist steel frame and vast walls of glass that completely dissolve the boundary between the home and the horizon. The Stahl House perfectly captured the glamour and optimism of post-war Los Angeles, becoming an enduring symbol of California modernism. It wasn't just a house; it was a statement about living on the edge of possibility.

"Building is a messy process," Koenig once said, hinting at his preference for steel's precision. "It is full of mud and waste and nails that get dropped. I try to make it as ordered and logical as I can."

While many of his peers were focused on industrial logic, Richard Neutra brought a deep concern for human psychology and well-being into his designs. A pioneer of what he called "biorealist" philosophy, Neutra believed that architecture should connect its inhabitants with nature to promote both physical and mental health. His work is a masterful blend of clean, geometric forms with the untamed natural world.

Neutra designed several homes for the program, including Case Study House #20, the Bailey House. He was a master of siting his buildings, carefully orienting them to maximise light, views, and airflow. Features like sliding glass walls, extended rooflines that created shaded patios, and his signature "spider leg" posts that stretched the structure into the landscape were hallmarks of his style. For Neutra, a home was a therapeutic environment, a carefully orchestrated machine for living well.

These architects, along with others like Craig Ellwood and Eero Saarinen, formed the creative heart of the program. All told, the initiative produced 36 designs, with 25 structures actually built between 1945 and 1966, mostly concentrated in Los Angeles County. Their combined efforts did more than just produce a series of remarkable buildings; they created a whole new language for residential design.

This new language was open, connected, and endlessly inspiring, much like the vibrant artistic movements influencing other areas of design at the time. For a fascinating contrast to the architectural minimalism of the Case Study era, you might be interested in exploring the work of Josef Frank, whose colourful patterns were making waves across the Atlantic.

You can't point to just one thing that makes a Case Study House special. It's the whole package—a thoughtful blend of design ideas that came together to create something completely new. These homes all speak a common architectural language, a sort of shared DNA that makes them instantly recognisable. It's a language built on honesty, efficiency, and a deep, abiding respect for the outdoors.

To really get what makes these places tick, you have to look past the beautiful photographs and see the thinking behind them. This wasn't just about looks; it was a practical philosophy for living better, solving real-world problems with elegance and simplicity. The architects stripped away all the fussy, needless decoration to focus on what truly mattered: light, space, and a more modern way of life.

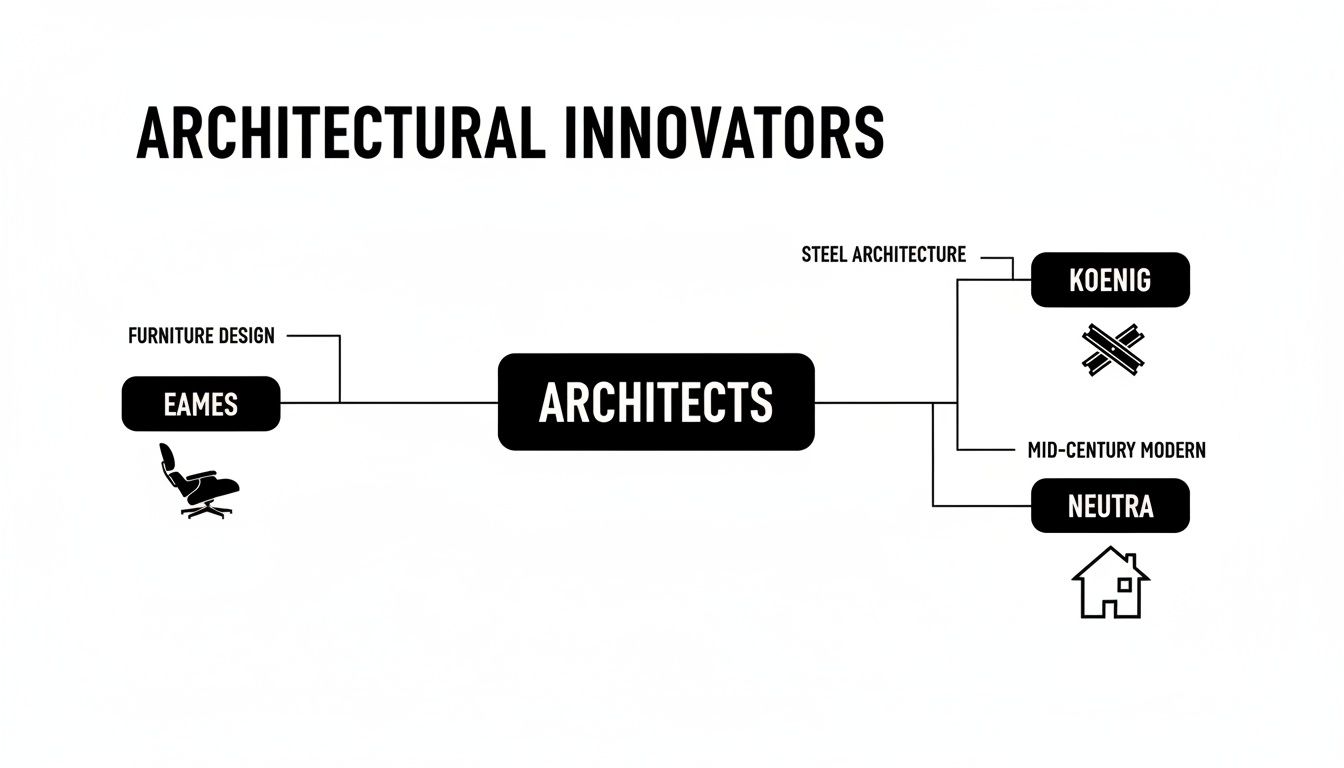

This infographic gives a quick overview of some of the key innovators and what they brought to the table.

As you can see, it connects architects like Koenig directly to the materials, like steel, that became fundamental to the architectural DNA of these homes.

Perhaps the most striking feature of many case study houses is their embrace of industrial materials, especially steel and glass. Architects like Craig Ellwood, an engineer by training, used exposed steel frames not just for structural support but as a core part of the aesthetic. This created a clean, minimalist grid that gave the home its form.

That strong steel skeleton is what made the other signature element possible: massive, floor-to-ceiling walls of glass. These weren’t just big windows; they were transparent skins that dissolved the boundary between inside and out. The effect was incredible, making even smaller homes feel airy, expansive, and completely drenched in natural light.

Take Case Study House #16. Ellwood’s design used its steel frame and glass panels so masterfully that the home seems to almost float in its garden. You’d never guess it’s only a 1,664-square-foot house.

Inside, these homes threw out the stuffy, compartmentalised layouts of the past. The architects championed open-concept floor plans where the living room, dining area, and kitchen all flowed into one another. It was a direct response to the post-war desire for a more informal, connected family life.

This open approach wasn't just a trend; it solved several problems at once:

More than any other architectural movement before it, the Case Study program perfected the idea of indoor-outdoor living—a concept tailor-made for the gentle climate of Southern California. This was so much more than just sticking a patio on the back of the house. Architects deliberately designed the homes to make the garden an active part of the living space.

Sliding glass doors were key, allowing entire walls to vanish and merge interior rooms with outdoor terraces and courtyards. Rooflines often extended far beyond the walls, creating shaded outdoor "rooms" that could be used nearly all year. Every choice was made to draw your eye outside and encourage a seamless flow between the built world and the natural one.

This fusion of industrial materials, open layouts, and a profound connection to nature is what defines the architectural DNA of the case study houses. It was a complete vision for a simpler, brighter, and more integrated way to live that, frankly, still feels radical and relevant today.

The minimalist elegance of the Case Study Houses provides the perfect canvas for your personal story. With their clean lines, natural materials, and wide-open spaces, these homes were never meant to feel cold or sterile. On the contrary, they are an open invitation for warmth, texture, and individual character.

The real art is in honouring the home’s architectural soul while making it feel completely your own. It’s a delicate balancing act: introducing personality without ever overwhelming the home's essential design. This is how a piece of history becomes a comfortable, living home.

Those expansive glass walls and simple material palettes practically beg to showcase unique, handcrafted objects. Think of the architecture itself as a gallery frame for your personal collection. A single, vibrant piece of art or a deeply textured sculpture can become an incredibly powerful focal point in a room defined by steel and glass.

This is where artisanal objects, like Scandinavian folk art, can really sing. Their organic shapes and handmade details create a beautiful, human counterpoint to the precise, industrial lines of the architecture. Just imagine:

These kinds of pieces add layers of story and personality, ensuring the minimalist backdrop never feels impersonal.

The goal is not to fill the space, but to punctuate it. Each object should have room to breathe, allowing its unique character to complement the home’s strong architectural lines.

Beyond specific objects, introducing a variety of textures is absolutely crucial for creating an inviting atmosphere. The original architects often used materials like rough-hewn stone for fireplaces or rich wood for accent walls, giving you a built-in foundation of natural warmth to work with. You can build on this by layering in softer elements.

Consider adding flowing linen curtains that gently diffuse that bright California light, or a plush velvet armchair tucked into a reading nook. A few sheepskin throws draped over a sleek leather sofa can completely change the feel of a room. These additions soften the hard edges of the architecture and make those grand, open-plan spaces feel cosier and much more intimate.

The magic truly happens in the interplay between hard and soft, old and new—that's what gives a Case Study house its soul. For more ideas on creating a curated space that reflects your own character, you might find some useful principles in our guide to man cave inspiration. By carefully selecting pieces that tell a story, you can bridge the gap between historical design and contemporary life, making one of these iconic houses feel uniquely yours.

It’s easy to look at the Case Study Houses program and think it fell short. After all, the grand vision of creating factory-line prototypes for the masses never really took off. But to judge its success by the number of homes built is to completely miss the point. The program’s real triumph wasn't in manufacturing; it was in capturing the popular imagination and forever changing residential architecture.

These weren’t just buildings. They were powerful, tangible ideas. Thanks to the pages of Arts & Architecture magazine and some truly stunning photography, concepts like open-plan living, indoor-outdoor connection, and the honest use of industrial materials were broadcast to a global audience. As a media event, the program succeeded wildly, altering what people thought a home could be.

The public’s fascination was immediate. Launched in 1945, the program commissioned 36 prototype designs to address the post-WWII housing boom in Southern California, with 25 of those homes actually getting built. In just the first three years, the initial six completed houses drew an incredible 368,554 visitors. People lined up to tour the fully furnished models, a clear sign of a huge public appetite for modern design. You can discover more insights about the program's history on Wikipedia.

The legacy of the Case Study Houses is really a story of inspiration, not replication. Architects and designers all over the world absorbed the principles showcased in these California homes. The open-concept layout, now practically a standard feature in modern homes, can trace its popularity straight back to this experiment.

The same goes for the seamless flow between indoor and outdoor spaces. Suddenly, this became a central goal for architects working in all kinds of climates, not just sunny Los Angeles. The program proved that a home could be a tranquil sanctuary deeply connected to its natural surroundings—a philosophy that feels more relevant today than ever.

These homes also showed that good design wasn't about fancy ornaments or huge expense. It was about intelligent, elegant solutions that made daily life better. By stripping architecture down to its essentials of structure, light, and space, the Case Study architects created a timeless aesthetic that still feels fresh and forward-thinking.

The program's ultimate achievement was ideological. It democratised modernism, taking it from an abstract, avant-garde concept and presenting it as an attractive, achievable, and distinctly American way of life.

Today, the surviving Case Study Houses are more than just architectural relics. They are highly coveted private residences and protected cultural landmarks. Many of the roughly 20 remaining houses are listed on historic registers, ensuring they'll be preserved for future generations. Far from being static museum pieces, they are lived-in homes that continue to demonstrate the durability of their original designs.

Their status has only grown with time, turning them into icons of mid-century cool. You’ll spot them regularly in films, fashion shoots, and advertising, cementing their place in our cultural lexicon. The Stahl House (CSH #22), with its jaw-dropping views over Los Angeles, is probably the most famous, becoming a visual shorthand for sophisticated California living.

The continued interest in these homes also taps into a deep desire for authenticity and thoughtful design. In an era of mass-produced housing developments that often lack character, the Case Study Houses stand as a powerful testament to a clear architectural vision. They remind us that a home can be a functional shelter and a work of art all at once. For instance, the exposed steel framing in many designs adds a striking visual element, a concept you can explore further in our article on incorporating metal artwork for your wall.

Ultimately, the Case Study Houses still matter because the questions they tried to answer are the same ones we're asking today. How can we live more simply, more connected to nature, and in spaces that are both beautiful and efficient? The brilliant answers this bold experiment provided continue to inspire and guide us.

To really get a feel for this landmark architectural programme, let's tackle some of the questions that pop up time and time again. This is where we get into the nitty-gritty: the core purpose of the Case Study Houses, the practical side of seeing them today, and the real-world reasons the experiment eventually wrapped up.

Think of this as your practical guide to completing the picture, whether you're a seasoned design enthusiast or just curious about these famous homes.

At its heart, the Case Study Houses programme was a creative solution to a massive problem: the huge housing shortage after World War II. Kicked off by Arts & Architecture magazine in 1945, the challenge was thrown down to leading architects of the day: design and build efficient, affordable model homes perfect for the average American family.

The whole experiment was about proving that modern materials like industrial steel and new ideas like open floor plans weren't just for fancy one-off projects. They could create homes that were both beautiful and budget-friendly. It was a direct, design-led answer to a national crisis.

The core mission was to make good design accessible. This wasn’t about creating luxury villas, but about crafting a blueprint for a better, more functional, and more beautiful way of life for everyone.

This vision was incredibly ambitious but perfectly timed, capturing the hopeful, forward-thinking spirit of the post-war era. The goal was nothing less than to redefine the family home.

For all the buzz and critical praise they received, the homes never hit the mass market. A few key hurdles stood in the way. The biggest was money; traditional banks and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) were simply unwilling to finance such unconventional designs. They felt much safer sticking to standard wood-frame construction.

These innovative materials and layouts just didn't fit the established formulas lenders used to assess risk and value. This financial roadblock was probably the single biggest reason the programme’s commercial dreams never took off.

On top of that, the custom nature of each design—along with the specialised materials—made them more complicated and pricier to replicate on a massive scale than anyone had hoped. Ultimately, the programme was a phenomenal success as an architectural experiment, but it just wasn't destined to become a commercial housing solution.

The programme officially commissioned 36 designs, but not all of them made it off the drawing board. All told, 25 of the Case Study Houses were actually built between 1945 and 1966.

Today, it's estimated that around 20 of these houses are still standing, almost all of them in and around Los Angeles. Many have been beautifully preserved and are now cherished historic landmarks, though some have been altered over the years by new owners. Their survival ensures that the legacy of this important architectural experiment continues to inspire.

The numbers really tell the story of both wild enthusiasm and practical reality. The public was fascinated—an incredible 368,554 visitors flocked to see just the first six homes within three years. But with banks hesitant to offer loans without FHA backing, the path to mass production was blocked. You can dig into a deeper analysis of the visitor numbers and financial challenges in this detailed university overview.

Yes, but it's tricky. Most of the houses are private homes, so you can't just knock on the door asking for a tour. Opportunities to see them up close are quite limited.

That said, a couple of the most iconic ones do welcome visitors:

For the other houses, you're pretty much limited to what you can glimpse from the street. If you're planning a trip, always check the official websites for the Eames Foundation and the Stahl House first for the latest tour information and booking rules.

At Dalaart, we believe a home's character comes from the unique stories it tells. Just as the Case Study architects designed spaces for modern living, our handcrafted Dala horses bring centuries of Swedish tradition and artistry into your home, adding warmth and personality to any interior. Discover a piece of authentic folk art to make your space truly your own by visiting Dalaart.